Why the word ‘Tokophobia’ is a problem

2nd August 2025

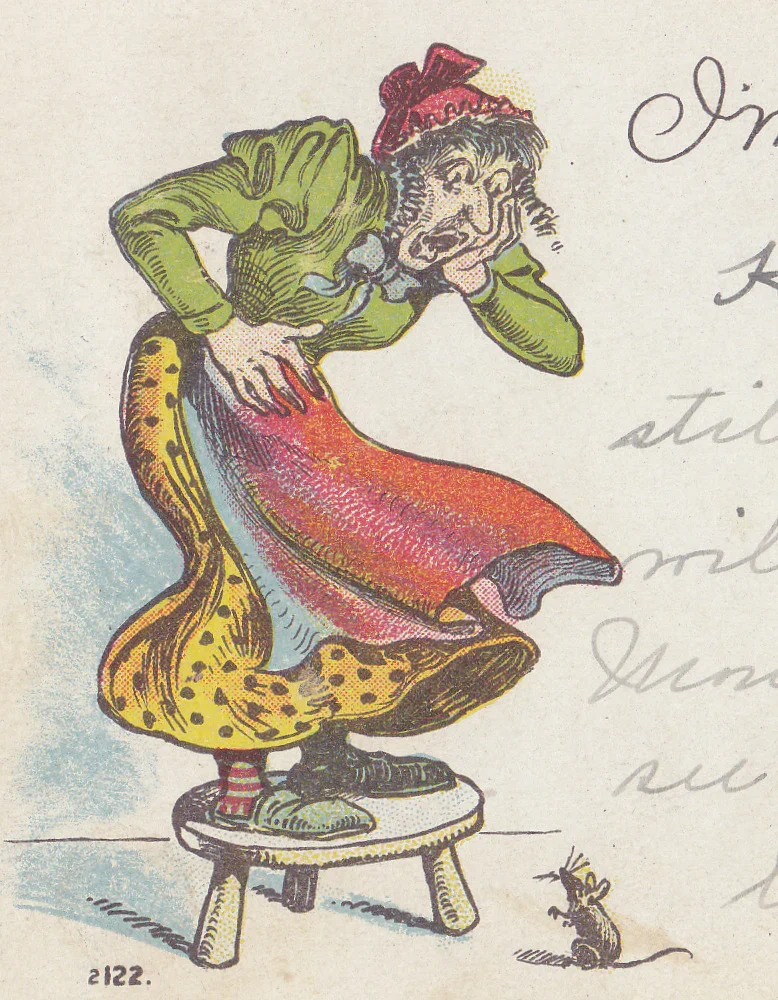

What are you scared of? Personally, my biggest phobia has always been centipedes (this link is to another blog, NOT a photo of a centipede!). I learned to cope with the tropical millipedes whilst living in Malawi, they are actually quite cute and in the local language are called Bongololos. A name which makes her sound like a many-handed extra in a marching band who just mooches around the forest eating leaf mulch, waiting for the call from her agent. I’m also totally fine with pretty much all other invertebrates - I am the one woman spider liberation front in our family and I took a large praying mantis landing on my shoulder with a calm not reflected by my partner, who screamed like the young day-tripper who invariably discovers the body at the start of an Inspector Morse episode. But centipedes. I, for one, take a stand that eight legs is a sufficiency and more than that is merely sabre rattling. I have a friend who is scared of cats, a family member who is frightened of fish (both living and edible) and my son has a mate with an irrational terror of baked beans. This is what a phobia is. There is no real reason for me to be scared of a rare, albeit horrifyingly alien, insect who probably doesn’t want to hang out with me any more than I would with Nigel Farage.

But more and more in my practice and in the wider discourse of the birth world in the UK, I’m coming across the word ‘tokophobia’ - the fear of childbirth. I am not a mental health professional. As a care leaver I’ve had my own mental health journey and I am still continuing to experience the joy and power of post-traumatic growth. But I haven’t studied psychology since A level, when me and my friend Shyam spent most of our time in class making fun of the odd shape of our teacher's head, to the detriment of my ability to remember who Pavlov was and why he had so many pets. I would never present myself as a clinician with more than the basic understanding of mental illness as appropriate to my work as a midwife. This post is not about the complexities of mental and physical suffering caused by our current birth system. PTSD, postnatal depression, complications in subsequent pregnancies are all on the rise and no one is disputing this. If you need support with these issues The Birth Trauma Association is a good place to start. This post is about how we are increasingly blaming women and birthing people for this harm.

Let’s go back to the context for this. We know that the UK has crossed the obstetric threshold whereby iatrogenic (medically caused) harm has overtaken the number of lives saved by the use of operative births a long time ago. We know that over-intervention is currently not just blossoming but has a tree canopy so high and roots so deep as to be an entire ecosystem of expensive, unnecessary and harmful procedures which cause mental and physical harm to whole families. In 2024, by NHS audit (so this is not statistical extrapolation, this is counting…) 43% of babies were born by cesarean section and a further 10% by instrumental (ventous or forceps) delivery. This means that babies born by ‘spontaneous vaginal birth’ (SVB) are now a minority in Britain. The word spontaneous cracks me up in this commonly used abreviation - very few people who have ever pushed their baby out would describe the experience as spontaneous, much as it can be joyous, its definitely a intentful and laborious process! Over my two decades in maternity I’ve seen the complex medico-cultural and political drivers of this trend manifest in practice and increasingly people are choosing to birth outside of the system, with independent midwife care or freebirths on the rise. However, these options are not affordable or possible for many people and decisions based on the imperative to avoid further harm are not free choices, even if the result is in the end a positive experience.

I am not against intervention. I’ve worked in several countries where ‘Too Little Too Late’ has led to young mothers dying avoidable deaths in my arms, and the faces of their families still haunt my darker days. Also, interventions can be non-traumatic. Real, informed choice and Human Rights based care is what is necessary here. I’ve had clients chose elective ceasarian sections for their own reasons and found the experience to be both positive and supportive of their parenting. Emergencies can and do happen and with the right team, with the parent as the main agent of decision making, they are not inherently psychologically scarring in and of themselves. As Poincaré said, "To doubt everything, or to believe everything, are two equally convenient solutions; both dispense with the necessity of reflection,". Only he said it in French.

The epidemiological discourse, that the increase in ‘aging and obese’ primiparous (first time) mothers are responsible for the current situation is one big public health fallacy and makes the common mistake of conflating correlation with causation. Changes in demographics that alter health outcomes are often causatively bi-directional, and complex issues require complex interventions. Yes, population shifts do change medical needs, but the upward trend in both age of first pregnancy and BMI in the UK is not nearly large enough to explain the massive change in mode of birth outcomes above. Again, babies born by SVB are now a minority. If anyone wants, I’ll happily do the maths on the current data. Further, overall wellbeing, including weight, is inherently a product of social inequality and the UK is a more unequal society now than when your nan gave birth. Given the racialised (read: racist) discrepancies in harm for pregnant Women and People of Colour, we also know that there is a lot more going on here than just population health trends.

But the word Tokophobia literally means an extreme and irrational fear of childbirth. Perinatal Mental Health Services now routinely offer groups for people with tokophobia. ‘Birth reflection’ services by units, which can be done well and provide postitive healing, are unfortunately often experienced as yet another go around of the justification for why over-intervention in your birth was deemed necessary and can further compound your feelings of powerlessness and fear of death; the two awful ingredients to bake PTSD. Emergencies can be iatrogenically created. For instance the overuse of synthetic oxytocin is a known issue, and then the service may position itself as having ‘saved you’ from the PPH (bleed after birth) you may not have had at all, if a more careful and holistic consideration (and informed, non-coercive consent) to using the drug had happened in the first place.

Of course true tokophobia exists. If a person has managed to get to conception without ever having heard the stories of their friend’s and family, read any newspapers or watched a soap-opera and still has a fear of birth, go right ahead and use the word. But I’m skeptical that this is a common situation. People also have complex relationships to their own bodies and this can profoundly influence how they feel about pregnancy and birth. Much more importantly and beautifully, I meet so many pregnant women and people who have had personal or vicarious experiences of birth trauma and approach their own journeys to parenthoods with a strength, optimism and deep love which never fails to make me realise how incredibly lucky I am to be a midwife. Being a midwife keeps my love of the human spirit alive, which in these times is a blessing far beyond that which anything proasic, such as an adequate salary, could provide. But we need to talk about tokophobia and call it what it really is. In the vast majority of cases it is not an irrational fear but a reasonable and rational response to a perinatal service which, on the whole, can no longer provide optimal physiological birth support. It is victim blaming. If we want real change, we have to first shout to turn this discourse around. And also a global campaign to eradicate centipedes please. Those hell-dwellers can do one.

The Polar Expedition

One thing that I am increasingly noticing is that now I have brought my work, my joy and my abilities into line with my own ethics, is that it is much easier to be gentle with people. To sit with our differences. Midwifery is, and probably always will be an emotionally charged experience. The skills to hold a strong love in the birthroom, and then the strength to occasionally navigate life and death decisions in this place of love and trust is probably unique to our profession. Though maybe one can feel a little like this in other adventures. The silent frozen tundra, captivating and wildly dangerous. The Sahara (in which I once got lost, but my camel, Jimmy Hendrix, found me) again a place of edge magic, beauty and of unstable footing. One mistake could cost everything. The responsibility is, frankly, huge.

As midwives we exist in a liminal space. Right up against the boundaries of tradition and innovation, of responsibility and autonomy. Of individualised care and ‘one size does not fit anyone’ protocols. Of the art of instinct and evidence-based practice. At our foundation we sit between the light and the dark of new life and tragic loss. I returned to the NHS for a few years in 2021 (after ten years of academic life) and the pervasive fear that everyone felt was palpable from the start. A fear often expressed though a new level of the coercion of families into increasing iatrogenic harm. As a wise doctor once told me, don’t just do something, stand there and think about it!

The ecological fallacy is a useful concept here - that something may be true on a population level but not apply to this individual. For instance, the link between smoking and certain kinds of lung cancer is pretty irrefutable now (thanks Doll and Hill) but we all know a Nana who smoked 40 a day and is still the funny and friendly matriarch well into her 90’s. This doesn’t disprove the smoking and cancer link, but it is extremely important to know that there will always be some people who are that Nana. But it works the other way as well, an onslaught of new ‘Nanas’, too many outliers, will change the epidemiological evidence in its turn.

Back in scrubs (or ‘Battle Pyjamas’ as my partner calls them) I saw how people, good people for the most part, took decisions about what care to offer pregnant people, based on a genuine belief that the offer was in that person’s best interest. And often they carried on offering and offering and then got their superiors to offer a bit more forcefully, finally offering the choice between their plan, or a ‘potentially dead baby’. Which is no choice at all. The fabulous Debs Neiger recently did a great article about why telling people to ‘just say no’ is like telling a cyclist that they should just refuse to let the bus swerve into the bike lane and run them over (my example, Deb’s post is a lot less satirical and more grown up).

The removal of the caesarean rate targets this year, nationally set, was in my opinion theoretically a good thing. An emergency procedure should never be unavailable or staff unwilling because we have had too many this month. Sorry, we’re up to our appendicitis quota, come back in November! That said, one of my local units had a caesarean section rate of nearly 50% last month. We can identify the proportion of the population of women and people needing a caesarean - the WHO estimates this as about 15% of births. What we cannot do is control the near random incidence of an individual turning up on labour ward tonight who will need a caesarean. Even harder, we don’t always know who that person will be until after it is needed or has been done. Therefore, whilst we are all making this decision to move to surgically expedite a birth based on the pregnant woman in front of us, the unconscious collective has decided, one woman at a time, that a 50% caesarean rate is ‘necessary’.

We do not always understand the statistical concept of ‘risk’ in maternity. That literally means, what is the probability of an event occurring. It is entirely possible that if you repeatedly dropped your toast on your cat (I did just that this morning, a bit bleary eyed and her looping my legs) it would land jam side down in her fur 1000 times. Annoyed and sticky cat aside, it is very improbable, but possible that the next 1000 cats would be jammy too.

Random distribution can look like a pattern and humans find that confusing too. I had a lovely colleague who had been a midwife for 25 years. She looked after three women with a uterine inversion in one month. She was taken to task for this, was she doing controlled cord traction too hard? Was she ‘guarding’ the uterus? She never had another one. So that’s about an average number of this rare event over a career course. She just got all her ‘average’ quota in four weeks. Unlikely, but if there were no context specific factors (confounding variables), then one happening exactly every 10 years is just as probable.

But the problem is that because now we are all so afraid of these events, of unit enquiries, of a disciplinary, even of just a Datix, we have become ‘risk averse’. If by this, we mean trying to prevent a random event then it really just becomes about fear. Of course patterns and context matter, Of course a decade of underfunding and underinvesting in the next generation of midwives has created dangerous levels of understaffing. This context is dramatically increasing the risk of families’ poor outcomes and traumatic experiences. I am absolutely not claiming that every outcome is distributed randomly. But because of the fear, and a lack of sector wide understanding about the relationship of the individual to the population, we have collectively raised the threshold by which we deem a vaginal birth to be ‘safe’. In doing so, we have interrupted the psycho-physiology of birth to such an extent that we are beginning to feel that such a thing as an emotionally safe, uninterrupted birth must be unattainable. That means that 35% of women and people in my local unit are experiencing iatrogenic harm for no gain, if the (well grounded) WHO estimates are correct.

What is more worrying is that maternity has completely confabulated a difference between iatrogenic morbidity (and mortality) and ‘natural’ morbidity. So, if I assist at a birth and the woman has a 3rd degree tear, I have to submit a Datix and usually someone will give me a good bollocking for it. If someone else does not experience cervical dilatation as a continuous linear process (rather than step wise, which I’m sure we’ve all seen sometimes) they get hauled out of the pool, put on a bed and on a CTG so we can administer oxytocin. If that someone then ends up with a bilateral episiotomy for a trial of forceps in theatre for suspected foetal distress. Then that someone has a second stage caesarean section, permanently damaging her cervix and bladder, and leading to an MOH, then that’s ok. That’s just what we needed to do to save mother and baby. The baby’s cord gases were absolutely normal, by the way, and the baby required no resuscitation. The mother however, did.

Ironically, and I’m not directly criticising the very necessary unit enquiries here, the urgent need to improve safety has led to an even greater increase in fear led unnecessary procedures and thus iatrogenic harm. ‘Normal at any cost’ is an oxymoron, similar to a Northen Trust who shall remain unnamed who had the phrase ‘Excellence as Standard’ as their branding. Standing in the corridor shouting at signs for being so patently ridiculous does not make you look sane, I found. It’s so annoying isn’t it, that 50% of people remain below average in the Trust Public Relations department.

So much of maternity has become polarised like this, both in the way we conceptualise care offerings and in the way we regard each other. It is beyond childish to say that all births will require no professional intervention, though of couse some do not -with the exception of keeping the snacks coming. I’ve worked in places where even basic interventions were not always available and step up care was virtually non-existent. However, the literally insane extent of over intervention in the UK is also an emergency of our own creation. To much too soon, to little too late.

Similarly, the obdurate discussions between midwives and birthworkers with views on racialised inequalities; gender identities; class and wealth; any topic with need and pain and loss at its centre, is also splitting us in two. All of us unable to hear each other because of the overwhelm of putrefied opinion that has come out of Political propaganda. We’re just gonna be over here with our £3000 glasses guys, you lot make sure you keep those pesky Black women/poor people /immigrants/LGBT+ peeps from stealing your stuff. Not a new idea by any means, but unfortunately still a relevant one.

Years ago, I bought a book for a friend, who had just qualified and got her fresh new midwifery wings. I wrote in it that birth can be the cradle of feminist empowerment or the crucible of gender oppression. I meant it as a slightly show offy little catchphrase. But right now, here in UK maternity, we have a battle between this cradle and the crucible. A battle which is increasingly reducing everything to a debate of extreme positions. This is an emergency. We desperately need to heft some the polar bears down or carry the penguins up (yes, I did have to google which one lived in the North Pole). And even more we need to have a gameplan that includes supporting , sitting with and valuing different people with different views of birth and the strong love of us all. We have become so polarised that we are eating each other alive. Much like the suddenly delighted bears, as they find themselves surrounded by all those tasty little black and white snack birds.

Invoking vocation

A while ago my partner found this photo, the full shot is of a group of nurses who were working in a field hospital during the First World War. There is a division in the weird blended queer found family about how much she looks like me. Personally, I agree with my partner, it looks like I time travelled back to 1916 and got myself a starched hat. I’m allergic to ironing though so they probably would have spurned my crumpled uniform.

Over the last few years I’ve been thinking a lot about what being a midwife means. In leaving academia, running the Sheffield Maternity Co-operative and now being ‘self-unemployed’ as an Independent Midwife and an International Health Consultant. The Co-op was an experiment in what anarchist community centred co-production of maternity care might look like. We achieved so much, both locally with projects like free training (from the amazing Abuela Doulas) for Doula’s and Birthkeepers of Colour in Sheffield and nationally with our Cultural Safety training. I think we must have directly reached nearly two and a half thousand maternity staff. There were many midwives; professional leads; student midwives; junior and senior doctors; midwifery support workers; and one very sweet but confused anaesthetist.

Being on the ‘sidelines’ though, with the co-op and now as an IM and freelance researcher, is giving me a strange sense of perspective on the behemoth institutions which govern so much of how we mobilise health care at one end and ideologize humans and their bodies at the other.

This could be a blog about the patriarchal and deeply colonial origins of medicine in late capitalism. It could be specifically about how we as a society judge and actively shape the female body. It is not uncommon for me to start listing all the eponymous names of female genitalia. Who the f**k is Douglas? Why is it his pouch? Who gave Bartholin the right to stick a metaphorical flag on both sides of my vagina? The only manoeuvre I know that is named after a midwife or even a woman is the Gaskin roll, my preferred second line (immediately after MacRoberts - see, another dude!) to release the posterior shoulder in a dystocia. And in all the text books now, it’s named the ‘all fours’ manoeuvres. Just so it’s clear. We make medical students learn what the islets of Langerhans are, and apparently that’s fine. But hey, hey, let’s not confuse people with a name for someone turning around, guys.

This isn’t what this blog is about. Mainly because I’m not currently ranting. It’s about what it means to have a vocation, to be a professional, to take on a mantle that is something bigger than you. A mantle so that is heavy that sometimes it consumes who you actually are.

We are inculcated in our training with the need to not just act in a professional way but to become a professional. A whole quarter of our NMC Code is a section on ‘Promote Professionalism and Trust’. It is fascinating that these two, quite different, aspects of a moral being are conflated here. Why is a professional demeanour more trustworthy? Why is homogeny in act (The Code) and appearance (uniforms) so important to the nursing and midwifery professions? Why is scalability desirable and industrialised processes so integral to us and to the wider health services?

I have said, and heard others say, well, you need to make sure you’re getting the same service in Cardiff as in Cambridge. Why? What if the needs are different? What if the metrics by which we both track outcomes and assign funding to are not applicable to many communities? I’ve seen countless excellent homebirth and caseloading teams and services shut down with the reason ‘we can’t do this for everyone’. Yes, of course everyone should get the best, the safest, the most empowering care possible. But this is not going to look the same in different contexts. Whilst we continue to operate in a system that is manifestly under resourced then yes, we have to take hard decisions about where we allocate resources. But the insane logic of ‘we can’t give this to everyone, everywhere so we’ll give it to noone’ is not a response to scarcity. It is a response from a system that fears individuality.

We talk a lot now about authenticity, about ‘showing up’ about the Roar! I’m fully in favour of all these things. I’m also in favour of intellectual pursuits and the importance of criticality (which is not the same as criticism). It’s a shame the academic sector has monetised and functionalised intellectualism out of all real meaning. I’m still a recovering academic, just one sniff of that markerboard pen and dusty papers and I’ll be using the word ‘dialectic’ again without a valid license.

Why then, do we continue with this archaic, and at it’s heart capitalist, way of both providing and measuring health care? When we are not our own selves in the birth space, we are implicitly not allowing others to be either. When we form connections why do we feel that they have to be ended to move on? The co-op which didn’t fundamentally know what it was, was a glorious confusion of light and laughter. Now being an IM I feel that I have ‘permission’ to bring at least some of my own personality to the work. I’m working with an incredible birthkeeper who I trust because I know how awesome she is, not because she interchangeable with anyone else. I’ve also just sent a mum a seven paragraph text on vaccination schedules and epidemiology so maybe I also need to be a little more succinct, you’d have to ask her. I’m sure she’d tell you who I really am.

Flamingos and forms

So here we are, 2024 and now an Independent Midwife (IM) and a Reproductive Medicine Consultant. Most of these blogs will be about the midwifery though, if you have any interest at all in the science bit then www.maternityinternational.org is also me.

The move to IM is a change I’ve wanted to make for the entirety of my nearly two decades of midwifery, and leaving the NHS has been a strange experience in and of itself. There are so many NHS rituals; 10.30am ‘free’ toast, never say the Q word; a total guarantee that at least one of the people eating Milk Tray chocolates will describe it as ‘naughty’. I’ve wanted to be an independent midwife so badly; it seems strange that I never quite felt I was ‘ready’ yet. In a sadder way, leaving the NHS right now felt like the only option, there is so much fear, so much iatrogenic harm, so little conversation about human rights. Moral injury is a concept that we desperately need to talk about because it is bringing so many excellent midwives to their knees and often out of maternity.

On a more positive note, there has also been some change and growth in me, some of it intentional, some of it just getting older (which is not the same as growing up, obviously). Whenever I start a new venture, I love the unexpected joy that comes with new situations, as well as the more predictable benefits that I am aiming for.

I’m so looking forward to being there for all the births people have booked me for, so enjoying the fact that there is a real and authentic sense of co-production, especially the power of the triad - Me (midwife), Chi (Doula and MaMa) and the amazing families we are working with. A sustainable and mutually supportive circle. I’m reconnecting with wonderful midwives who have been such an inspiration to me too.

And of course, there are some bits of midwifery which will never change - I gave up about 10 years ago on the promise that one day we would have decent, accessible and quick digital documentation. I mean, writing everything down four times, one of which WILL be on a paper towel, is just who we are now. But also, there is the fun- I was not expecting that, laughter and mutual trust being central, not superfluous. And I bought a new pool thermometer with a flamingo on top who keeps reminding me of this new fun and lightness. What do we want? More flamingos for birth!